Catching Hell / Greg F. Gifune

Cemetery Dance / May 2010

Cemetery Dance / May 2010

Reviewed by: Blu Gilliand

Catching Hell is a difficult book to pin down. It starts out feeling like a coming-of-age/road trip story as we join three good friends (plus one hanger-on) getting ready to spend one last summer weekend together before going their separate ways. It veers quickly from there into a classic horror scenario: that of the strange town in the middle of nowhere, the one that seems stuck in the past and is filled with mysterious-to-the-point-of-creepy residents. From there, it detours into yet another story type familiar to horror fans, one that I’m reluctant to spoil here. Suffice to say it leads into the story’s final transformation into a survival tale, albeit one with a Twilight Zone-type twist at the end.

Pulling off such schizophrenic storytelling is no easy task, but for the most part author Greg Gifune is up to the challenge. He takes the time in this compact tale (number 20 in the Cemetery Dance novella series) to build solid, likeable characters in Billy, Stefan, Alex and Tory before throwing them into chaos, which is important in a story like this — if you don’t care what happens to the group, you really don’t care what happens in the story. That’s not to say they couldn’t have used a little more fleshing out — Tory, in particular, is more stereotype than true character, saddled with the mellow mindset and laid-back surfer-speak straight out of Fast Times at Ridgemont High. Still, the fast pace of the story helps gloss over some of these deficits in character development.

The one true qualm I have with Catching Hell comes with the revelation of what is really going on in this strange little town of Boxer Hills, that third story shift that I don’t want to give away. It’s not what is happening, necessarily – although it’s not exactly original, it’s certainly a rich enough situation that familiarity isn’t a bad thing – it’s how the characters discover the truth of what’s happening to them. It’s just a little too convenient having your characters literally go into a library and immediately pull down the exact books that explain most of what is happening to them. This occurs in a single chapter about midway through the book, and it really brought the story to a halt for me. Instead of the mystery that drove the first half of the book, we suddenly know almost everything there is to know, and the book goes from discovery and survival to a simple race against the clock. Don’t misunderstand — it’s a taut, well-written race against the clock, but the heavy exposition that gets us there just takes away from the whole experience.

Catching Hell is not without its problems, but it does have quite a bit working in its favor. Gifune keeps the story running at a quick pace, and the tension of the slowly unfolding situation is palpable throughout the first half of the book. From the moment the group leaves the library the tension is still there, but it’s changed; that amazing sense of unreality that keeps the characters off-kilter is gone. It’s a shame, because up until that point the book was a can’t-put-it-down thriller. From then on, it’s merely good — not a bad thing, of course, but still so far from what it could have been.

Purchase Catching Hell by Greg F. Gifune.

Blood Splattered and Politically Incorrect / Del James, Brian Keene, Thomas F. Monteleone and Lee Thomas

Cemetery Dance / December 2010

Cemetery Dance / December 2010

Reviewed by: Daniel R. Robichaud

Cemetery Dance Publications' Blood Splattered and Politically Incorrect is a chapbook anthology of four short stories. This saddle stapled volume comes as a signed edition limited to 750 copies. As the title suggests, the contents employ potentially offensive themes and situations — its stories wants to upset you, and therein lays the potential pitfall.

Shock alone has a short shelf life before it becomes rather boring. Tales that intend to offend need to work double hard to engage their readers. After all, a story that doesn't entertain is not going to hold the reader long enough to draw them through to the punch line. Blood Splattered and Politically Incorrect is typical for an anthology, in that some stories succeed better than others.

The opening piece is Del James' "Sick Puppy." James is the author of The Language of Fear collection, originally released in the 1990s under Dell Books' Abyss imprint. His most well-known piece is probably "Without You," cited as the inspiration for the Guns N Roses' "November Rain" music video. James' works are concerned with the same themes and subjects as the original splatterpunks; they present fast paced, urban horror stories peopled with social outliers — punks, wastrels, and the downtrodden. "Sick Puppy" is firmly rooted in this tradition. It relates the many failings and setbacks of a nameless, diseased, junkie narrator. Though it begins on the ugly, realistic side of life, it soon delves into the supernatural, when a drug trip preludes a horrific encounter. After this, the narrator receives horrible power, and spends the remaining story discovering its limits and uses.

"Sick Puppy" is delivered with a raw, often unfocused style. It bounces between wildly divergent topics, offering up voluminous research atop a thin plot. While this builds a decent sense of the uncertain world and times the character lives in, this reviewer found very little insight into the narrator himself. The piece is all surface, little depth, so when it delves into the realm of bloodletting and shocking horror, it is unsuccessful at stirring the emotions. The ending is meant to resonate, and yet it leaves me wondering just who this story is intended for. The piece is told first person, but why are we hearing it? While the story has a few moments worth visiting – particularly the opening sequence, which offers the single instance of empathy for its protagonist when he watches the televised images of the 747s destroying the Twin Towers on 9/11 – "Sick Puppy" never really gels into a memorable story.

Brian Keene's "A Revolution of One" is pure rant. Its unnamed, first person narrator makes gleeful attacks on whitebread America's proclivity for banality and passivity. The piece's structure is deceptively simple, repeatedly delivering a "This Is Why You Fail, but I Succeed" argument, which builds to a world changing revelation.

Keene began his career with confrontational message board antics, blog posts, and prose (e.g. 2002's Talking Smack), and "A Revolution of One" reveals the years have not tempered his rancor but have honed his ability to deliver it. Though this piece is not quite a story in the traditional sense – there's no real plotting involved, unless one makes the stretch that the reader is intended to be the protagonist, and the narrator the antagonist (or vice versa) – it still held my attention. This is a neat trick since the "you" the "I" talks to is about as far removed from me as possible. Brevity is a saving grace here. As anyone who has suffered a message board flamewar knows, if left to go on too long, a rant grows tiresome. "A Revolution of One" knows when to stop, and it does. While it might not satisfy everyone, I found it an entertaining way to kill a couple of minutes.

Thomas F. Monteleone's "Real Gun Control is Hitting What You Aim At" targets Rowe Carlin, an advocate for gun control, affirmative action, school vouchers, etcetera, etcetera. This journalist soon discovers his liberal beliefs put to the test when an intruder breaks into his house. What follows is a gruesome comedy of errors, wherein Mr. Carlin finds himself drowning in trouble until he arrives at the not-unexpected ending.

This piece aims to deliver a tongue-in-cheek assault against hypocritical pundits. Unfortunately, the protagonist falls into the too-stupid-to-live category, so the conclusion lacks any real punch. Were Carlin an actual character instead of a straw man caricature capering as the plot-engine demands, this piece might have had some real bite to it. Alas, its teeth have been pulled.

With "Testify," Lee Thomas delivers a powerful piece about hypocrisy and homophobia. It begins with a corpse in an Austin apartment, and then delivers the back story. At the heart of this tale are Reverend Robert Wright, a well known anti-gay religious leader (modeled in no small part after Fred Phelps), and his lover Jimmy "Angel" Royce. When Wright's relationship comes to light, it ignites a storm of controversy, building to murder.

Instead of providing a single viewpoint character, "Testify" presents all its information through over twenty sources, including social media updates, personal statements, newspaper quotes, and other documentation. The result is akin to flipping through a well-made scrapbook, which pulls a coherent story from disparate material. "Testify" is a jigsaw puzzle of inconsistent viewpoints and opinions, recalling such compelling crime fiction mosaics as Jim Thompson's The Criminal and The Kill-Off. Perhaps its finest success is in asking interesting questions that linger after the entertainment is done. Thoughtful and compelling, "Testify" is the standout piece in this anthology.

Shock fans looking for sizzle will find something to enjoy in each of the pieces. Those readers eager for strong storytelling will likely be less satisfied with Blood Splattered & Politically Incorrect. Then again, this anthology knows its preferred audience — the title doubles as a warning label.

Purchase Blood Splattered and Politically Incorrect, with stories by Del James, Brian Keene, Thomas F. Monteleone, and Lee Thomas.

The Ones That Got Away / Stephen Graham Jones

Prime Books / November 2010

Prime Books / November 2010

Reviewed by: Vince A. Liaguno

Reviewing the works of Stephen Graham Jones is a daunting task. Not because of any shortcoming or lackluster aspect that requires the careful deliberation of words but because the work, quite frankly, is so brilliant at times that it demands the most circumspect, most diligent of analyses. To put it another way: A review of Stephen Graham Jones’ work necessitates living up to the quality of the work itself. Anything less would feel…well, somehow unacceptable.

Indeed the thirteen tales that comprise Jones’ cerebrally chilling short story collection require refreshingly more from the reader than your run-of-the-mill compendium. And, yes, while there are glimpses of comfortingly familiar genre tropes sprinkled throughout The Ones That Got Away in the form of zombies and werewolves and ghosts aplenty, there is nothing comforting or familiar about the context and texture in which Jones wraps them. The situations his characters – who are achingly real at times – find themselves in are painful and discomfiting in the best sense of the words. In turn, the reader is challenged to keep up, to survive the horror with his characters, even when it’d be easier to simply close the book and set it aside on the nightstand. Laird Barron, in his able introduction to the collection, characterizes its literary ambiance perfectly:

“The Ones That Got Away is a slippery collection; it resists and gnaws at the bonds of genre, yet may be the most pure horror book I’ve come across. The cumulative effect of these stories includes dislocation and dread — the manner of dread that arises from what is known by our soft, weak, civilized selves through rote and sedentary custom and symbolic exchange of cautionary fables, as well as a deeper, abiding fear of the ineffable that’s the province of the primordial swamp of our subconscious.”

Dislocation takes center stage in the collection’s first offering, “Father, Son, Holy Rabbit”, in which a father and his young son are lost in a snowy wilderness. Although the unsettling cannibalism at the story’s center is masked within the boy’s delusions of heroic bunny rabbits that provide sustenance in their dire circumstances, there is a gorgeous humanity here in the form of the lengths of a father’s love for his son juxtaposed against how childhood minds can mask the cruelty of adult realities.

The resiliency of the child’s mind also factors heavily in “Till the Morning Comes”, in which an uninvited houseguest comes calling in the form of a hippie uncle – complete with a collection of Grateful Dead-style velvet posters sporting creepy skeletons that greatly unnerve the story’s twelve-year-old narrator. When a spooky story involving a Dad who sings to dead kids in the back of a VW bus wreck spurs more than the narrator’s sudden onset bedwetting, Jones ratchets up the familial tension to the breaking point. “Till Morning Comes” is a shining exploration of the lengths children will go to keep the skeletons that frighten them in the closet where they belong and a heartbreaking tale of how families are pulled apart and put back together again.

In “The Sons of Billy Clay”, more cannibalism as a veteran prison guard regales –then horrifies – his young trainee with tales of the souls of bloodthirsty killers trapped inside bulls. Jones shows a real flare for spot-on dialogue in this prison-set, Southwestern-flavored campfire tale.

“So Perfect” finds Jones revisiting his patented pitch-perfect present tense narrative structure that feels deceptively experimental while really sporting quite a polish. He nails the Pretty Little Liars-esque narcissism and catty banter of adolescent girls in this cautionary tale about body image run amok. And ticks. Lots of icky, creepy-crawly ticks.

“Lonegan’s Luck” exemplifies Jones’ sharp knack for blurring genre lines, here taking the Old West and infusing it with modern-day zombies in this story about a nomadic snake-oil salesman who peddles his own unique brand of zombie virus to unsuspecting, God-fearing townsfolk. In classic woman-scorned style, Jones doles out satisfying dollops of literary comeuppance in this thoroughly entertaining genre mash-up.

Cujo meets the living dead in “Monsters”, a surprisingly poignant coming-of-age tale during which first love blooms with nightmarish consequences. This at-once relatable “one of those magical summers…” stories is easily one of the best examples of Jones’ ability to creep the reader out and then suddenly wallop them with a profound dose of humanity that threatens to rip the heartstrings from the chest. Consider the unadulterated gorgeousness of the following passage in which Jones goes from horror to humanity in the space of a single (albeit long) sentence:

“I swallowed, my eyes full with what had happened, with who, or what, I’d led to Elaine, with what he might be picking from his teeth right now in whatever dark place he was holed up in for the daylight hours, and then, to make up for it, to start making up for it, I draped my new granddad’s arm across my shoulders, to help him up the hill, and understood a little even then, I think, about what it might be like to have spent your whole life alone, so that just one person reaching up to help you along could mean the world, and save your life, and make everything all right for a few moments.”

In “Wolf Island”, a shipwrecked werewolf, some playful dolphins, and a killer whale are the unlikely characters that populate this story of lycanthropes versus marine life — with a surprising winner. Jones’ work here perfectly illustrates his uncanny ability to throw seemingly random ingredients into a pot and yet somehow manage to serve a literary stew impeccably balanced in flavor.

A cancer-riddled homicide detective is on the hunt for a seeming anthropophagic serial killer in “Teeth”. Perfectly blurring the lines between reality at the story’s start and surrealism as his protagonist’s disease process progresses with the story, “Teeth” is (again) infused with subtle hints of humanity. When the detective wonders if the animal control facility he’s visited earlier in the day leaves lights on for the animals at night, Jones adds marvelous depth and dimension to what could be – in lesser hands – a forgettable stock character.

The Stephen King influences are on fine display in “Raphael”, which sports some of the best introductory paragraphs you’re likely to ever read in a camaraderie-amongst-teenage-outcasts story. Think It or “The Body” or even Dreamcatcher in spots and let Jones morph into the master for a few thousand words and carry you through this tale of an unsettling childhood mystery that becomes a heartrending adult tragedy.

What can this reviewer say about “Captain’s Lament”, Jones’ Black Quill Award-nominated tale of merchant marines and urban legends? Well, this.

In “The Meat Tree”, Jones brings that forlorn face-on-the-side-of-milk-carton (or, in this case, on a flyer stapled to a telephone pole) to life in this story of damaged children growing up into broken adults. With childhood demons in hot pursuit at every trippy twist Jones lobs at the reader, aimlessness and obsession collide with extortion, vegetarianism, and one man’s quest to find himself — quite literally. One of the more cerebral offerings in the collection that will require some mental calisthenics before, during, and after the reading experience.

In the collection’s titular story – and its shortest – Jones paints a bleak picture of wayward teens awash in juvenile delinquency. One botched kidnapping mistaken for a home invasion later, childhood itself becomes the harbinger of lost opportunity that follows the story’s protagonist into adulthood. Caution: Recurring theme ahead.

Jones seemingly takes each striking element from the dozen stories that precede it and with “Crawlspace”, the collection’s closing novella, offers a master class in short fiction. An ingenious premise (a baby monitor as an otherworldly conduit), a lead character so well-drawn that you think he’s actually in your cell phone contacts by story’s end, an air of mystery (here revolving around paternity) mixed with a palpable sense of tension (here involving infidelity amongst friends) all make for a page-turner of unexpected proportion. Again, Jones will jump out at the reader from amidst the spooky goings-on to surprise with a penetrating reflection on the humanity of his characters, this time giving keen voice to the comforting intimacy of friendship between men and the bittersweet hopefulness of shared dreams:

“Quint laughs, rubs his dry bottom lip with the back of his hand, and joke-punches me on the shoulder, and for a moment it feels like I actually wasn’t lying the other week — that we are all still the same. That our kids are still going to be born the same year, to grow up together like we did. That our wives are going to sit in the kitchen with weak margaritas while we burn things on the grill, one of us always running down to the store for ice and beer. Taking just whichever truck’s parked closest to the road.”

Jones is really a maverick among today’s dark fiction writers, his writing style brilliantly nonconformist while remaining engagingly accessible. The Ones That Got Away is the perfect showcase for his wide-array of literary acrobatics and eccentricities that often fall just outside genre boundaries yet always seem firmly entrenched in darkness, each story in this exceptional collection a cerebral Ritz cracker to feed the farthest corners of the darkest mind.

Purchase The Ones That Got Away by Stephen Graham Jones.

Willy / Robert Dunbar

Uninvited Books / January 2011

Uninvited Books / January 2011

Reviewed by: Paul G. Bens, Jr.

A dilapidated school in the middle of nowhere. An encroaching winter. Dozens of troubled, teenaged boys, some violent and some...perhaps not. Add in an old and dying Dean of the school who’s been secreted away and an enigmatic boy named Willy — who seems to strike fear in the hearts of all the adult administrators — and you have all the makings of a classic horror/suspense piece. The question is, will the author take the clichéd route, or will he take those elements and weave them into something complex, fascinating and utterly suspenseful? Lucky for readers, Robert Dunbar, author of The Pines, The Shore and Martyrs & Monsters, is never one to take the road most travelled, and with Willy, Dunbar doesn’t disappoint, giving readers a novel that is challenging, full of dread and peopled with characters both appealing and frightening.

Shuffled from one “school” to another, an unnamed narrator is our guide, the events of the novel unfolding via entries he makes in a journal suggested by his previous therapist. Though the boy himself doesn’t understand the worth of it all, he dutifully — almost obsessively — tells his story as he finds himself at yet another facility, one as broken and out of place as he himself seems to feel. Often disjointed in tone and focus, these early entries reflect a stream of consciousness fragmented by transience and capitulation to the world around him as the boy’s attention is drawn from one thing to another at the drop of a hat. The result is a jarring narrative that keeps the reader off balance, leading one to wonder what his boy might have done and what he might yet do.

Dunbar’s dedication to the boy’s voice is unwavering, capturing the essence of a young man beaten down by life, numb to it almost, and the conceit works well. Our narrator catches only snippets of things the adults around him say and seems only to acknowledge his surrounding to the extent he needs to in order to survive. Largely, the adult supervisors and teachers are dismissive of him, looking down their noses at yet another “troubled youth.” It’s a label and attitude the narrator has not only come to expect, but one which he has begun to believe about himself. He is nothing more than an inconvenience — hardly a person at all — a case to be passed from one institution to another as he teeters on the brink of insanity.

He is assigned a room in the institution amidst whispers and a sense of fear that grips the adults, though one is never sure why. It seems that our narrator’s roommate is, perhaps, the worst of all the problem kids:

But the black lady wasn’t laughing anymore. “We can’t be putting him there,” she kept repeating. “You know what I’m saying.

Though the adults seem afraid to even whisper his name, the titular character is, no doubt, to be the young man’s roommate. But Dunbar doesn’t introduce us to Willy for quite a while, his absence going unexplained. Instead, the reader is given a chance to let their imagination run wild as they wonder what horrible thing Willy could have done to have landed here and, more importantly, what he did to deserve such a protracted absence from the school. In short, Dunbar lets us construct our own monster, indulging our voyeuristic tendencies as the narrator discovers Willy through his belongings and through the cryptic comments of the ever-present adults. By doing this, Dunbar builds a slow, methodical sense of dread, a palpable suspense that is really quite masterful. When we meet Willy, we are certain he’ll live up to every horrible thing we’ve imagined.

But Dunbar pulls the rug out from under us. When we finally meet Willy, he’s not some axe murderer or psychopath; he’s affable, fiercely intelligent and incredibly charismatic. He soon bonds with his new roommate, and Dunbar builds a remarkable relationship between the two, one reminiscent of that between James Dean’s Jim Stark and Sal Mineo’s Plato from Rebel Without a Cause. As in the cinematic classic, there’s homoeroticism here, but more important is the dynamic of two “troubled” youths, one wise enough not to believe he is the offal the adults paint him to be. As Willy shows him his intrinsic value, our narrator begins to grow beyond the labels, embracing his intelligence and wit, and the journals entries slowly become more lucid and confident, driving the narrative.

Willy is clearly a leader amongst the boys. And that, perhaps, is what puts the adults around him so ill at ease. He is their Jack Merridew, intelligent and savage at the same time. But is he dangerous because of some unspoken, violent past? Or is it because he sees through them, knows all their little secrets, and is not content to take what they say simply because they have been placed in a position of power? We surmise there is something horrible in his past — mostly from the vague comments of the teachers — but Dunbar never reveals what it is, so we’re kept off balance throughout the book.

And when Willy is suddenly sent away, is everything exactly as it seems? The boys begin to unravel without their leader, the mansion seems more decrepit, and the adults are far less balanced than they should be. Amongst it all, our narrator is haunted by the memory of Willy. Or is it the ghost of him?

“Willy?” I moved really slow down the corridor and pushed the washroom door. “Hello?” I kept my voice soft so as not to scare him. Something rustled, and I went in, blinking at the light when I hit the switch. “Willy?”

Those familiar with Dunbar’s work will not be surprised at the complexity of this novel. He takes a simple premise and imbues it with a keen literary sense. Some readers might be put off by the fragmented style of the beginning of the novel, but by page 20 the voice and emotion of the narrator will grasp them. Dunbar excels at capturing the emotion of troubled youth and not a stick of dialog feels forced or out of place. He also manages to attach us to these boys, making us root for them although we know they are likely doomed...at least some of them.

While the adults that populate the novel are less sharply drawn, this is with reason. The adults pay little mind to the boys in their charge; likewise, our narrator has little use for them, seeing as he will only know them for a very short time before circumstances change again. Under Willy’s influence, however, he becomes more attentive to their whispers. He sees their dynamics, learns a little of their secrets and the political maneuverings within the school. Slowly he begins to see that they are no better than he and the other boys. In fact, they may be worse, their lives apathetic and passionless. This too serves to ratchet up the suspense as we find ourselves wondering what is going on behind those closed doors at night.

This reviewer also appreciated that Dunbar does not spoon feed the reader. We never really learn what it is that Willy or the other boys have done to land them in the institution. Dunbar knows that sometimes what is most frightening is what we don’t know or what we only catch glimpses of, that unknown something lurking in the corner, and he uses that well. In the end, it is inconsequential what they have done. It is what they have been made to be that is important.

There are a lot of unanswered questions throughout the novel, but never is it dissatisfying or frustrating. Expertly crafted, intensely moody and infinitely suspenseful, this is horror at its best, most fulfilling. If you tend to like your suspense and horror a bit on the simplistic side, with clear-cut good guys and bad, this may not be the novel for you. However, if you prefer well-crafted suspense with a literary style that is both cryptic and creepy, there is much here to appreciate in Dunbar’s latest — one that continues to haunt long after the reader puts it down.

Purchase Willy by Robert Dunbar.

To Each Their Darkness / Gary A. Braunbeck

Apex Publications / December 2010

Apex Publications / December 2010

Reviewed by Daniel R. Robichaud

Gary A. Braunbeck's second foray into book-length nonfiction, To Each Their Darkness, is a complex work that is at once a memoir, a reflection upon the writer's craft, a review of the highs and lows of horror entertainment, and a call to action for creators of dark fiction. While this book might easily lose its way trying to cover so much ground, Braunbeck's capable prose and emotional honesty hold the book together. The result is both thoughtful and provocative.

This volume owes quite a debt to Braunbeck's Fear in a Handful of Dust: Horror as a Way of Life (Betancourt & Company, 2004). In fact, Braunbeck reprints much of that book's material here. The author is quite upfront about this, elucidating the rationale behind revisiting his early work and the differences between the two texts through five humorous and self-effacing introductory explanations. In brief, Braunbeck views the current book as a variation on a theme, an attempt to better express the points the previous volume approached but missed. As Fear in a Handful of Dust was an expensive hardcover, Apex Publishing's reasonably priced trade paperback is a welcome edition.

However, To Each Their Darkness is not a lightly revised and minimally expanded variant on Fear. This book offers new material, including intros and afterwards (for works by Mort Castle, Glen Hirschberg, Fran Friel, etcetera), some musing on film adaptations, and a heartfelt tribute to horror fiction legend J. N. Williamson. In addition, readers will find plenty of erudite analysis of other writers' works, the current faltering state of horror fiction, and Braunbeck's high hopes for the field.

This book's central argument is one of self analysis: without understanding the darkest parts of one's own life, the book argues one cannot create something truly horrifying. Going one step further, the book turns Douglas Winter's infamous speech equating horror with emotion on its ear, stating horror is not an emotion at all, but a byproduct of other feelings. Thus, the Braunbeckian ideology of horror calls for a complex tapestry of emotions, responses, and relationships. Only through well drawn characters, can fear be communicated.

A book of this nature can be viewed in two wildly divergent ways: it is either a smorgasbord of encyclopedic knowledge and analysis about the honest value of horror entertainment as seen through one fan and creator's life and work, or it is a self-indulgent attempt to establish the importance of personal hobby horses to an indifferent world. I side with the former way of thinking, while accepting the existence of a vocal contingent for the latter: to each their opinion. These are the same responses granted to any work wherein writers grapple with the juxtaposition of fiction, film, and life, including Harlan Ellison's The Glass Teat, The Other Glass Teat, and Harlan Ellison's Watching, Stephen King's On Writing and Danse Macabre, David J. Schow's Wild Hairs, Joyce Carol Oates' Faith of the Writer and In Rough Country, and Larry McMurtry's In a Shallow Grave; To Each Their Darkness comfortably stands in these titles' company.

When the book works best, it draws together autobiography, film criticism, an aesthetic vision, and gallows humor to portray Braunbeck's own life and reflect upon this life as a source for the terrors populating his fiction. Stories, whether told through prose or pictures, do not exist in a vacuum — the better tales draw upon personal experience while responding to stories that came before and inspiring those that follow. Just as Godard could criticize a film by making another film, authors contribute to a grand conversation with each novel or short story they write. In its successful sequences, To Each Their Darkness shows one creator's process for contributing his individual voice to that ongoing discussion. Though it leaves little room for popcorn escapism – save for a cheeky introduction to Ray Garton's 'Nids and Other Stories, which feels oddly out of place here – these passages offer the clearest call for creators to aspire for larger things than yet another zombie-apocalypse or simplistic vampire tale.

Like the best of Braunbeck's fiction, To Each Their Darkness is intensely personal. As such, it won't be to everyone's liking, but this is a book that neither requires nor desires blind devotion. It is a curiosity, a puzzle that is at once illuminating and frustrating and confrontational but always engaging.

Readers who have not read Fear in a Handful of Dust: Horror as a Way of Life will find much to think about. Those familiar with that volume may be disappointed by the ratio of reprinted material to new, but in any form, this volume's ideas are well worth revisiting.

Purchase To Each Their Darkness by Gary A. Braunbeck.

Faithful Place / Tana French

Viking / July 2010

Viking / July 2010

Reviewed by: Martel Sardina

Faithful Place made this reviewer’s short list of “must reads.” After reading, French’s first two offerings in her series about the Dublin murder squad, the bar was set high for book number three.

French’s mystery series is different than most because it is the setting that binds the series together versus following the same character over the course of several books. In each of the books, French tells her story through the eyes of a different protagonist. The books work well as standalones. There is not much overlap in terms of characters and backstory from one book to the next. The common thread linking them all is the connection to the Dublin murder squad.

In French’s second book, The Likeness, readers are introduced to the character Frank Mackey. He is in charge of the Undercover assignment that Detective Cassie Maddox has been recruited for. In Faithful Place, readers are given the opportunity to get to know Frank better. The story French tells this time around, explains an awful lot about how Frank Mackey became the kind of man and kind of cop that would be willing to do the things that he’s done.

Frank left Faithful Place, his childhood home, more than twenty years ago. He’d meant to escape an abusive household by eloping with his sweetheart, Rosie Daley. When Rosie didn’t show up at their rendezvous point, Frank incorrectly assumed that she abandoned him and ran off to England on her own. Though devastated by the breakup, the thought of staying with his family and being forced into a factory job like his father was unbearable. Frank followed through on his plan to leave and never look back. For more than twenty years, he’s done a good job of staying gone.

Frank’s sister calls to tell him that Rosie’s suitcase was found when one of the new neighbors decided to remodel their home. Frank drops everything and comes back hopeful that the discovery might turn up clues about what happened that night. Later, when Rosie’s body is discovered, Frank is devastated all other again. She didn’t abandon him. She was murdered. Frank’s not sure which ending is worse. He vows to find out who killed Rosie Daly. But will that knowledge bring him peace?

There is much to like about French’s writing style, the characters she’s created and her insights into dysfunctional people. Her prose comes alive. Her dialogue is spot on. Where Faithful Place fell short for this reviewer was the mystery of “whodunit?” I knew who the “bad guy” was very early on. That did not keep me from finishing Faithful Place, but it was a bit of a let down in comparison to French’s first two books, where the “whodunit?” was not as easily solved.

Overall, Faithful Place is an enjoyable read. Those who have read and liked her other books should enjoy this one as well. While the books can be read out of sequence, those who are new to the series may want to start at the beginning with In the Woods, to see how the puzzle pieces fit together since French has chosen a different way to bind the books together over time.

Purchase Faithful Place by Tana French.

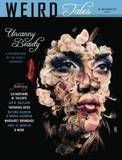

"Secretario" / Catherynne M. Valente

from Weird Tales #356 / Summer 2010

from Weird Tales #356 / Summer 2010

Reviewed by: Daniel R. Robichaud

With its first line, Catherynne M. Valente's contribution to Weird Tales' summer 2010 issue strips the noir genre down to its essentials:

"In the City, there are three kinds of people: the dead, the devils, and the detectives."

From here, "Secretario" fashions an unusual, dark story about the missing Mala Orrin, the City's lone female detective. The tale is related through two narrators — extracts from the detective's journal and a monologue delivered by her male secretary (who coins the story's title as the masculine noun for his occupation). Though only five pages long, the story presents multiple corpses, a couple of devils, clues aplenty as to the detective's fate, and an abundance of delicious mystery.

Valente's prose is as carefully crafted as ever. The piece deftly transitions between its narrators, using the different voices to craft both a doomed love affair as well as an odd mentor-student relationship. The result is immersive and engaging — one part epistolary and one part confession make for an intoxicating attention grabber.

"Secretario" has quite a bit going on under the hood. It turns gender roles on their heads. It is fascinated with archetypes, and its narrators are not shy about identifying or drawing classical references around them.

In this grim City, the dead are always women, the devils are always men, and only the detectives can swing to either sex. Such reductions raise questions about the detective's secretary: Is he a knight in training or a monster?

"Secretario" keeps most of its answers close to its chest, avoiding an exposition-heavy whodunit ending by fashioning a mood drenched piece from a noir fiction template. Down these rainy, mean streets walks a darkly fantastic vision, sometimes beautiful and sometimes chilling and recommended reading for dark fiction addicts.

Purchase Weird Tales #356 featuring Catherynne M. Valente’s “Secretario”.